I have always been fascinated by old books and their tooled and gilded bindings. Years ago, when I worked at an academic library in Cambridge, a favourite part of my job was to carefully rub a special kind of polish into the leather covers to keep them fed and supple. I would fetch the key to the climate-controlled, fireproof strong room in which the ‘special’ books were stored, select a volume which looked in need of attention, and get to work with a soft cloth. As I worked, I would marvel at the intricate designs, and above all at the antiquity of these objects – we held books dating back to less than a century after Gutenberg’s revolutionary invention of printing with moveable type, most of them in their original bindings. Whose hands had touched these covers and turned these pages before me?

Recently I was able to visit a remarkable exhibition at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth. Entitled Beautiful Books, the exhibition consists of twenty-two books and an accompanying film which shows the bookbinding process. Perhaps counterintuitively for a library, the emphasis is not on the content of the books, but on their bindings. Created between 1849 and 1993, the books showcase the talents of remarkable bookbinders whose work goes far beyond simply making covers to protect the words within.

For a few years, I subscribed to the Folio Society, and a number of attractively-bound limited edition volumes were added to my bookshelves. Apart from that, I have had little exposure to modern binding, and this exhibition was therefore quite an eye-opener for me. As I worked my way around the glass cabinets, a few themes emerged.

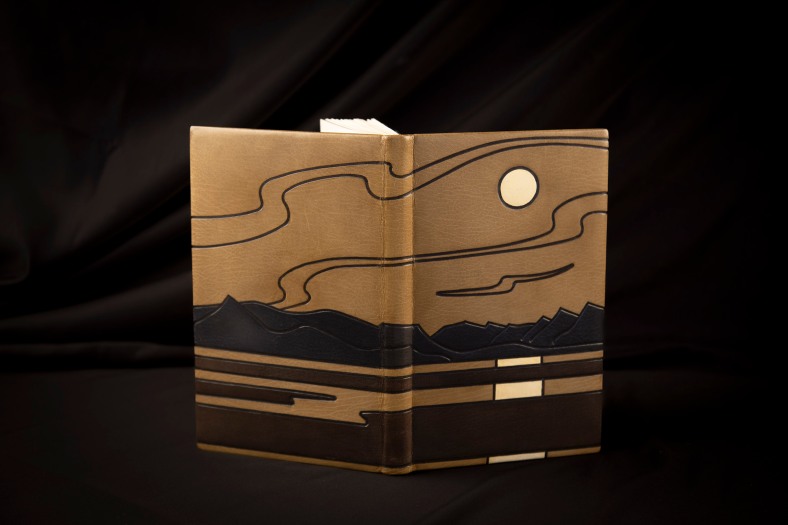

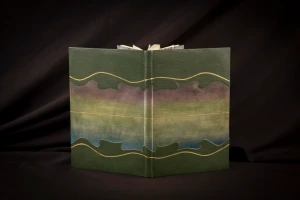

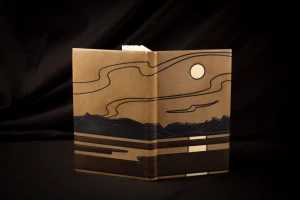

These bindings are works of art, and not just in the way one says of something impressive, ‘wow, that’s a work of art!’ These fine bindings create pictures, images, in way that is reminiscent of textile art. The use of blocks and lines of colour, gilding, texture, and motifs which respond to the subject of the book, combine to make artworks which stand in their own right.

Stylistically, they are very much of their time. For example, the binding by Elizabeth Greenhill for Louis MacNeice’s The Burning Perch (1963) put me in mind of a tapestry by Graham Sutherland, and would not have looked out of place scaled up on the wall of a brutalist concrete building on the South Bank in London.

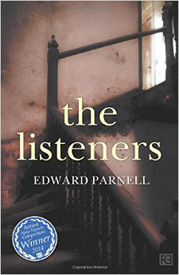

In many cases, it really is possible to judge the book by its cover, as the binding gives a hint or preview of the contents. For example, the cover created by Julian Thomas for Houses of Leaves, a translation of the work of fourteenth-century Welsh poet Dafydd ap Gwylim by Rachel Bromwich, published in 1993, takes its inspiration from the book’s title, and features lines based on the outlines of leaves and the tendrils of foliage which ornament medieval manuscripts. And with the binding for Across the Straights by Kyffin Williams, Thomas’ collaboration with arguably Wales’ most famous artist results in Williams’ essential simplification of landscape being expressed on the book’s cover.

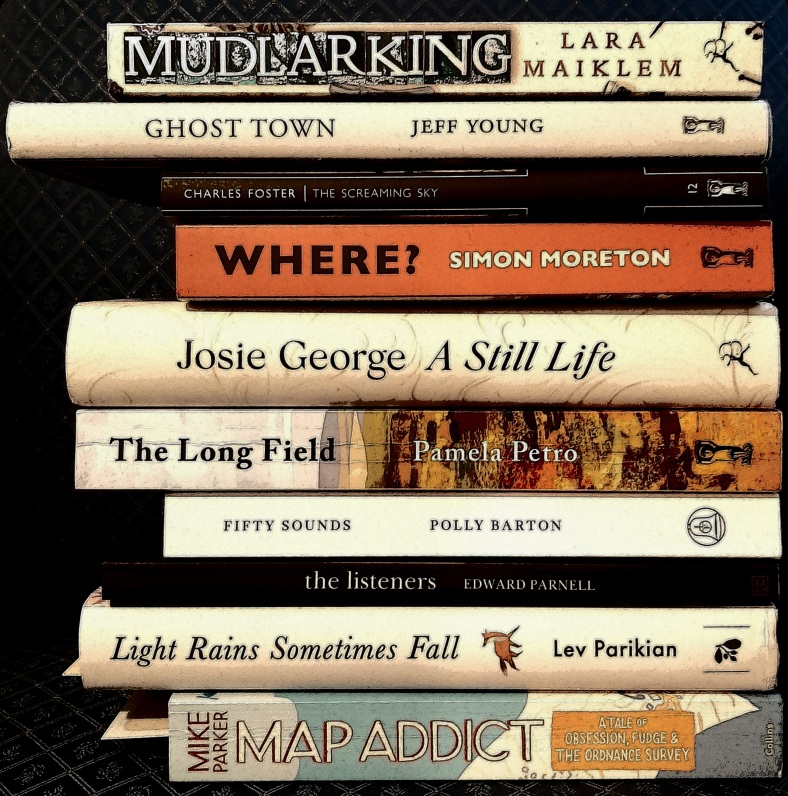

As a writer, it is a strange experience for me to be looking at books as artefacts as well as texts (or indeed as artefacts instead of texts – with the exhibits contained within glass cases, it is of course not possible to interact with the printed words within). This has made me muse about the books I own. Are some of these, too, artefacts rather than just texts? Do I choose to have them because they symbolise my aspirations to be knowledgeable, cultured, or well-read (whether or not I’ve actually read them)? Do some of them earn their place on the shelves because of the tactile quality of their bindings, or their attractive cover designs? There are certainly some books I have bought because I was entranced by their covers, and others where I have been pleasantly surprised when their plain, worthy covers prove, on actually reading the book, to belie the fascinating content. Book covers matter.

The exhibition Beautiful Books continues at the National Library of Wales until 9 December 2022- more details here: https://www.library.wales/visit/things-to-do/exhibitions/beautiful-books

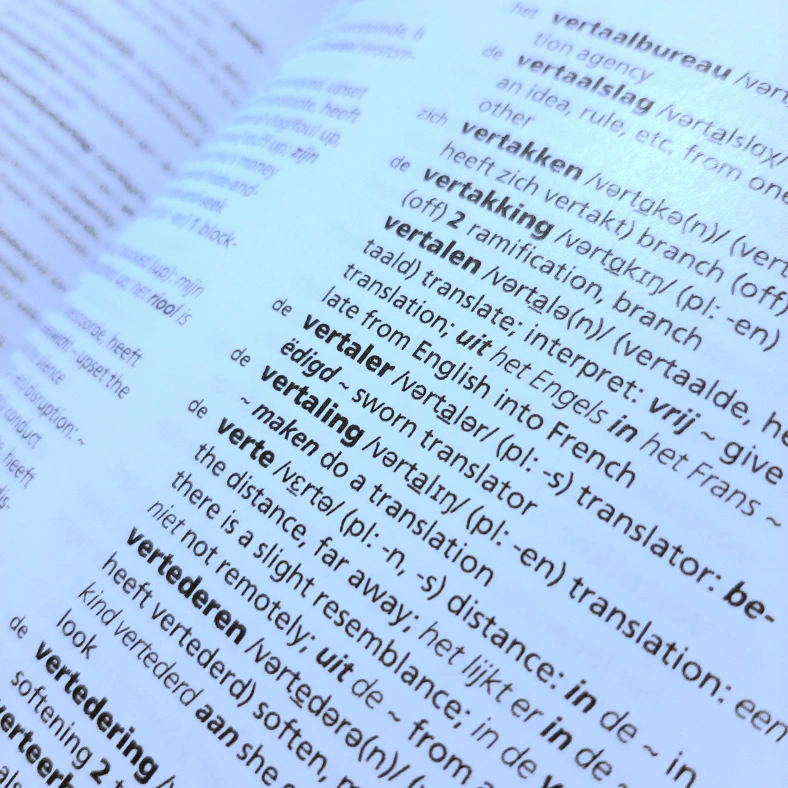

Just upstairs from this exhibition is another, which also caused me to think about the significance of books. Beibl i Bawb (A Bible for All) celebrates the four hundredth anniversary of the publication, in 1620, of the translation that became the standard text of the bible in Welsh until the 1980s. The significance of the Welsh bible goes far beyond religion – as with many languages, the standard translation defined the language, providing a benchmark for written Welsh and a foundation for cultural and literary life to the present day.

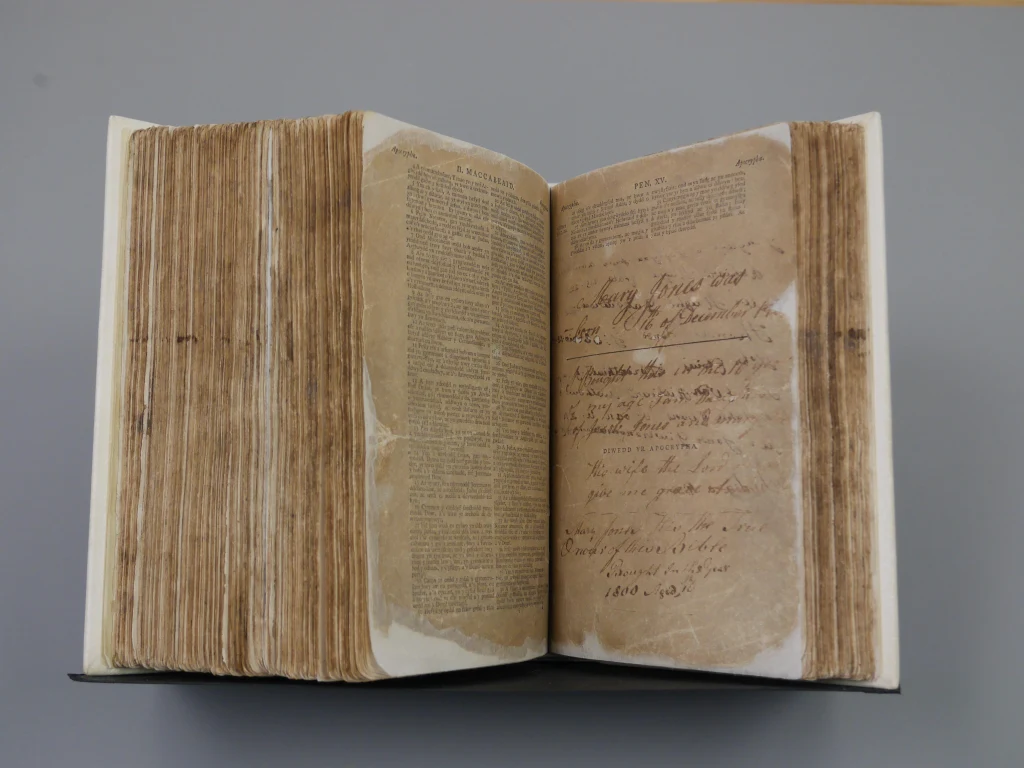

Here, too, I am brought face to face with the book as artefact. In this case, it is the bible owned by Mary Jones. Her barefoot journey across North Wales in 1800 to buy her own copy of the bible in her own language has become a story that is told across the world. This object – dark with use and age – is more than a book. It connects us to an individual, a real person who held it and turned its pages, and also to a whole history of a language and the people who speak it. And it tells the story of reading – at that time, Wales had one of the highest rates of literacy in the world thanks to the ‘circulating schools’ pioneered by Griffith Jones and his successors, which would come to a district for a while and teach people of all ages and genders to read, the aim being that they would be able to read the bible for themselves. Literacy was perceived as what we still know it to be today – the gateway to knowledge and independent learning that can change lives. Mary Jones’ bible is symbolic of the world of words and ideas that was opened up to her when she learned to read. There can be few greater gifts than the ability to read.

The exhibition Beibl i Bawb (A Bible for All) is on until 2 April 2022 – more details here: https://www.library.wales/visit/things-to-do/beibl-i-bawb

I am committed to making this blog freely available, and not putting material behind a paywall. As a writer, I am doing what I love – but I still have to make a living. If you have enjoyed this post, and if you are able to do so, perhaps you would consider supporting my work by making a small contribution via the Buy Me A Coffee button. Thank you!