This weekend sees the end of British Summer Time, when clocks in the UK go back an hour from GMT+1 to GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). The immediate effect is to make the mornings light an hour earlier, and at the other end of the day to make darkness fall an hour earlier too. It’s a shift which, every year, makes me mournful,.

British Summer Time is not a new invention. Benjamin Franklin mooted the idea of ‘daylight saving’ in the late 18th century, and it was first discussed in Parliament in 1809, but did not receive support. In 1907, however, a builder in the north of England by the name of William Willett, noticed while out riding his horse in the early morning that most people’s windows were still shuttered despite it having been light since before 4 a.m. This prompted him to publish a pamphlet entitled The Waste of Daylight, in which he suggested putting the clocks forward by an hour, so that the morning hours of daylight could be used productively. His ideas were eventually implemented in 1916, as part of wartime measures during World War I, although unfortunately Willett did not live to see it as he died of influenza in 1915. Germany had brought in Summer Time in 1916 to increase productivity, and Britain followed suit in May of that year, with British Summer Time set to GMT+1 and Winter Time remaining GMT.

In the days before combine harvesters equipped with floodlights, the lighter evenings also enabled harvest work to go on for longer into the evenings. The benefits to farming prompted the introduction of British Double Summer Time during World War II, with GMT+2 in the summer and GMT+1 in the winter.

From 1968-71 there was an experiment at leaving the clocks on GMT+1 all year round. Although there were suggestions that the overall effect on road casualties was positive, the introduction at the same time of other road safety measures made it difficult to evaluate benefits, and Parliament voted to end the experiment in 1971.

In 2002 the EU standardised the transitions between Summer and Winter Time, so that these took place in all member countries on the last Sundays of March and October, making time difference calculations easier for businesses working across borders. Although there are currently proposals before the Council of Ministers to end the time changes in March and October, with member countries choosing either their summer or winter times to continue throughout the year, these proposals have not yet been approved (and in any event, with Britain now no longer a member of the EU, they would not apply here). In Britain, there have been a number of attempts to end the changes and settle on GMT+1 all year round, but again, these have not become law. Controversy surrounds the evidence of the effects of darker winter mornings on road safety, especially around children walking to school, and also in Scotland and the north of England, where the effect would be to delay sunrise until mid-morning. It has even been suggested that England and Wales should have a different time zone from Scotland, for that reason. But for the moment, the current arrangements continue.

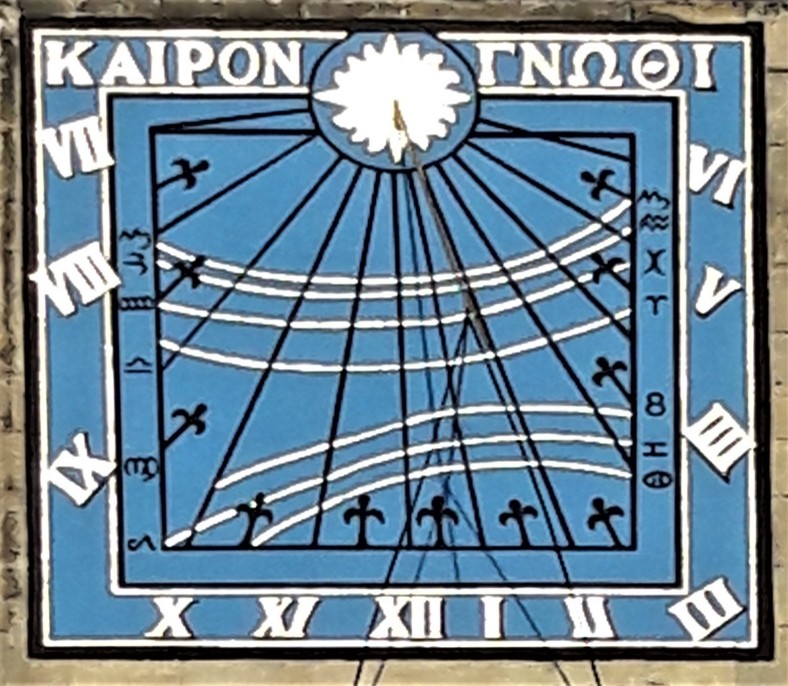

Sundial, Ely Cathedral

Willett’s concept of The Waste of Daylight uses the language of ‘daylight saving’, which I always thought a strange notion – as a child, I wondered if there was a savings banks somewhere which stored all that lovely daylight, and doled it out as required? Or would the daylight eventually run out if we didn’t ‘save’ it, like saving water or saving electricity? It wasn’t until, as an adult, I read the history of British Summer Time and its importance in the World Wars that it made any sense whatsoever. Because, to be honest, it’s always seemed crazy to me – why voluntarily plunge us in to dark evenings at precisely the point when the days are getting shorter anyway?

From about August each year I start to dread the end of British Summer Time. The days are already noticeably shortening, and the threat of losing a whole hour of precious light at the end of the day looms large. Frankly, I am not a morning person, and the whole business of getting up and going out to work (especially when this involves commuting) is so ghastly anyway that I don’t really notice the light levels as I’m in my own little dark cloud! But at the end of the day, when my time is my own and I could actually do something like going out for a walk after work, or pottering in the garden, or simply getting home in the light so that it doesn’t feel as if I’ve gone a whole day incarcerated in an office without daylight, having that last hour of light stolen from me really rankles.

It’s undoubtedly better since I have been working at home, with the freedom to organise my own day and take advantage of the daylight to go out when I want. But I still find the gathering gloom of winter mid-afternoon depressing. Putting the lights on so soon after lunch simply in order to be able to read feels wrong, especially since I know that it doesn’t have to be this way, that it’s only because somebody, somewhere, has decided to persist with this practice of plunging us prematurely into darkness each day for half the year.

Not everyone reacts badly to the end of British Summer Time, though. My partner tells the story of her late grandmother, who used to relish the early onset of darkness. She liked to draw the curtains, turn on the lights and settle down into the cosy glow of a winter late afternoon. At this time of year she would take down her summer curtains – light and bright – and replace them with winter curtains – thicker and warmer. I’d never heard of this practice before, but apparently many of her contemporaries did it too. I quite like this idea of embracing the positives of the early darkness, rather than my tendency to mourn the light evenings. I find it hard to celebrate the particular qualities of late autumn and winter, with their emphasis on home, interiors, creating cosiness and ‘hygge’, a kind of battening down the hatches against the more hostile seasons of the natural year, making a haven of light and warmth in the way that my partner describes from her childhood.

Of course there has to be darkness as a counterpoint to the light. We love the lengthening days of spring so much precisely because we are emerging from the darkness of winter. Without the cold of winter, with the trees bare and nature dormant, we can’t have the hopeful budding of spring and the abundance of summer. The almost endless days of Midsummer require the counterbalancing long darkness of Midwinter. My challenge is to adjust my thinking, to accept and appreciate the dark side of the year as much as the light side, and to find enjoyment in what autumn and winter uniquely bring rather than grieving for the light. This winter, I will try not to wish the days away until British Summer Time begins again.

I am committed to making this blog freely available, and not putting material behind a paywall. As a writer, I am doing what I love – but I still have to make a living. If you have enjoyed this post, and if you are able to do so, perhaps you would consider supporting my work by making a small contribution via the Buy Me A Coffee button. Thank you!