Recently I have been spending time in 1950. No, this isn’t some weird Lockdown experiment. Nor is it one of those popular history programmes on television, where a family pretends to go back in time to another era, where they invariably find that a) everything is much harder work than they are used to, b) the food is boring, bland and monotonous, and c) women have a considerably worse time of it than in the 21st century suburbia they are used to. My time travel is altogether more personal.

I have blogged before about the cache of family photographs and papers I inherited a while ago. Most of them relate to the maternal, Dutch side of my family. But there are just a few items from the paternal side, including, for some unknown reason, my grandfather’s diary from 1950.

This side of the family were Liverpool Welsh, part of the large community of immigrants from Wales which was a significant part of the population in the great port city of Liverpool, in the North West of England, from the middle of the 19th century. A large proportion of the Liverpool Welsh originated from the island of Anglesey, off North Wales, probably due at least in part to the island’s tradition of fishing and seafaring which would give them plenty of relevant skills for working in the docks. My grandfather was born on Anglesey into a seafaring family – he was just five years old when his father died when the ship he was skippering went down with all hands in Bardsey Sound in the 1880s. Although the details I was told by my father are a little hazy, there is documentary evidence that my grandfather was in the Merchant Navy at some point in his life, and also that he was the captain of a tug boat based in Bootle docks. I wonder how it felt to be able to see Anglesey across the water from the banks of the Mersey?

I never knew either of my paternal grandparents as they died long before I was born. Neither did I ever meet most of the cast of characters whose names are familiar to me from my father’s stories and from Christmas cards – aunts, uncles, cousins. But in this diary I get a snapshot of their lives, their preoccupations, their daily activities and their holidays, and little details such as my grandfather’s birthday presents (socks, a muffler and a neck tie). Several weeks of the diary are devoted to the business of getting electricity installed in the house, and frustration with Mr Jones, the electrician (presumably another member of the Liverpool Welsh community), who doesn’t turn up when he’s supposed to, and goes off for days at a time to work on other houses, leaving the place a mess and the job half done. It seems some things don’t change!

From my grandfather’s diary, I learn a lot of things I either didn’t know, or wasn’t sure about. One of my uncles is a coal merchant, and he and his wife and young son are obviously going up in the world as they are the proud new owners of a motorcar, a pre-war Rover 10. This same uncle upgrades his coal lorry, only to have an accident when his shiny new purchase collides with a tram cart on Derby Road, in the docks area, and has to be ignominiously towed back to the coal yard for repairs. One of my aunts, disabled by polio as a child and still living at home aged 43, goes on holiday to London and while there marries her pen-friend (a precursor of internet dating?). This event warrants only a couple of lines, and none of the family seems to have attended. Did she elope? It’s a possibility, but there is an intriguing sentence a month earlier, when the pen-friend is staying with them in Liverpool: “hoping for the best.”

There are some things which seem inconsistent to me. His world seems very small – every day consists of shopping and housework for my grandmother, a walk for my grandfather, various uncles, aunts and cousins visiting every day to do things like help carry the shopping home, scrub the doorstep or bring round the evening paper, taking it in turns to keep them company in the evenings. More than half of each day’s entry is pretty much a verbatim repeat of the previous day, and his life seems a far cry from the active 71-year-olds I know these days. But the family also travel extensively – I know from photographs that my grandmother visited London on holiday in 1948, and according to the diary in 1950 various family members have vacations in North Wales, the Isle of Man, and London (in the latter case, lodging with other members of the Welsh diaspora). They have a daytrip to see the Flower Show at Ruthin in North Wales (my grandmother’s home town). My father at this time is living in the South West, and my other uncle is at college near Sheffield, with placements all over England and even Ireland.

My grandfather’s spelling is positively Shakespearian at times, often phonetic, with a level of literacy which suggests he was not educated beyond elementary school. However, he reads the newspaper every day (including newspapers sent by relatives in other parts of the UK), and engaging with the written word through keeping a diary is obviously important to him. There are hints too that it is my grandfather who deals with the business correspondence for the uncle with the coal yard.

I find the nature of his Welsh identity enigmatic, too. For example, I know from my father that my grandfather was a first language Welsh speaker, but he chose to write his diary – that most personal document – in English. Where he does use Welsh, for example in place names, his spelling is every bit as erratic as it is in English! As with so many in the Liverpool Welsh community of the time, much of the family’s social life is based around Welsh-language churches and chapels, although by his own account my grandfather attends less than the rest of the family – he prefers to listen to Sunday morning services in Welsh, from chapels in Wales, on the radio.

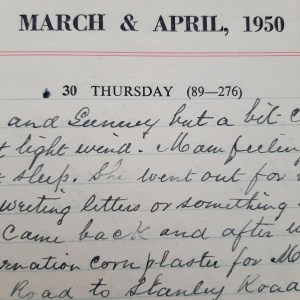

Each day’s entry starts with a report on the weather: “Very nice morning nice and clear not too cold, wind South West light” or “rather dull at first then rained hard, stoped [sic] some sunshine then more heavy showers and more sunshine. Wind about South West by South.” Along with occasional references to going to sign for his Seamen’s Pension, it’s the only clue to his years aboard ship, where the state of the weather – and the wind in particular – would have been of utmost importance.

I have written about the personal nature of handwriting, which gives an immediacy and intimacy that cannot be replicated by the typed or printed word. Through this diary I have spent time with someone who is at once both familiar and a stranger. I know of him, but almost everything I knew before reading this was mediated through my father, who was a fairly unreliable narrator. I never knew my grandfather – but although I never met him in person, I have here in my hand a book which he held, every day of the year. I have his words, written with a fountain pen, the quality of his handwriting reflecting his state of health on any given day. I can see where he has gone back and added in an afterthought, or corrected a mistake in the day’s chronology. This man is responsible for a quarter of my genes, and this is the first time I have had any physical contact with him. When I turn the pages, I am touching his fingerprints. This is the closest I will ever get to him.

The last full entry in the diary is for Boxing Day, Tuesday 26 December 1950. He writes:

“In the afternoon R and B came up for us all to go to there [sic] house for a party, but owing to the coughing and spitting I stayed at home. I hope that they will have a good time there.”

The following day he writes only “Nice day” – not even a weather report. Within a fortnight, just a few days before his 72nd birthday, he is dead.

I am committed to making this blog freely available, and not putting material behind a paywall. As a writer, I am doing what I love – but I still have to make a living. If you have enjoyed this post, and if you are able to do so, perhaps you would consider supporting my work by making a small contribution via the Buy Me A Coffee button. Thank you!