It grieves me that it took so long for me to get round to reading this book. I know Ed Parnell, and have read his non-fiction Ghostland, so I knew his debut novel would be good. But the arrival of my signed copy of The Listeners was followed closely by the arrival of Covid and the first lockdown, and I suddenly found it impossible to read fiction. It was as if the surreality of real life, with everything we took for granted suddenly swept away into an unknowable and dystopian future, seemed to make my brain incapable of coping with imagined realities. I had a large ‘to be read’ pile which included a number of fiction books by authors I knew I liked, but each one was closed and put aside after only a few pages. I just couldn’t hack fiction.

For a year and a half I read only non-fiction. Then, last summer, I started re-reading the Golden Age crime fiction collection on my Kindle (Agatha Christie, Dorothy L Sayers, Margery Allingham). These were safe, generally not graphically violent, with structures that were familiar and worlds which trundled along on their predictable tracks. All very comforting. Stella Gibbons’ Cold Comfort Farm, too. But it has taken until last week for me to feel up to tacking new, more challenging fiction. It was time to open The Listeners.

I love this book. I’m sad I’ve finished it – I eked out the last few chapters over several days, to put off the moment when it would be over. It is a treat, a gem, a perfectly-formed little treasure, like a beautifully crafted piece of work by a skilled artisan. It is utterly beguiling. And yes, I know that sounds hyperbolical, but I mean every word.

The Listeners is set in the wartime years of the 1940s in rural Norfolk – in an area near to where I used to live, so I recognize the descriptions of landscape and wildlife that provide the staging for the events of the book. It is not so much the events that carry the reader forward, as the voices of the various narrators who take turns to give their perspectives. It takes quite a while to work out which, if any, of the narrators are reliable. Much of the action is in the shadow of events up to a generation earlier, events which are only hinted at. The way those past events, and their implications for the present and the future, are gradually and subtly revealed to us is a masterclass in understated writing. At several points in the narrative, I had a sudden, nauseating jolt as I realized what was actually being referred to, what it was that had happened and was not being talked about, or what was, with a sickening inevitability, going to happen next.

It is, in many ways, a dark book. Anyone who has read Ghostland will know that Edward Parnell is an aficionado of the dark, the weird, of things hinted from the shadows. The Listeners, which predates Ghostland, should really be depressing – I can’t tell you about all the motifs because it would spoil the plot for you, but let’s say that most kinds of violence, abuse, betrayal and grief feature in it – but the writing is so beautiful and the characters so deftly painted that it glows with chiaroscuro like the work of an Old Master.

The pace is measured – a pace appropriate to country folk who are, despite the upheavals of WWII, simply getting on with the necessary cycle of the agricultural year and domestic life – but the book never drags. The change of voice with each chapter shifts our viewpoint, keeps the reader on their toes (and often doubting everything they’ve just read in the previous chapter). And the ending – with the reader now knowing something which the protagonists do not – is genius.

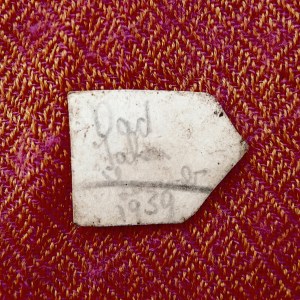

The Listeners (the title is borrowed from the poem by Walter de la Mare, for reasons which will be come apparent) won the Rethink New Novels Competition in 2014 – this is another reason why I am calling this a ‘belated’ review. The good news for those of us who are late to the party is that it is still available to buy (direct from the author at https://edwardparnell.com/buy-signed-copies/, or from Amazon as a print-on-demand book or on Kindle). I have reviewed a lot of books this year which I have very much enjoyed but, for me, this is my book of 2021. I just wish I could un-read it so that I could have the joy of reading it again for the first time.

I am committed to making this blog freely available, and not putting material behind a paywall. As a writer, I am doing what I love – but I still have to make a living. If you have enjoyed this post, and if you are able to do so, perhaps you would consider supporting my work by making a small contribution via the Buy Me A Coffee button. Thank you!