On the last weekend in April, I re-connected with my tribe. After a break of two years because of the pandemic, Wonderwool Wales was finally able to go ahead in its traditional slot of the last weekend in April, and nothing was going to keep me away. The event at the Royal Welsh Showground near Builth Wells in rural Mid Wales has taken place since 2006, and whilst it started with the idea of raising the profile of Welsh wool and providing a showcase for craftspeople and small businesses using wool, it has developed into a gathering of the fibre-obsessed from all over the UK and beyond.

Let me try to set the scene. The venue is three large barns which, when used for agricultural shows, are full of pens containing trimmed and brushed sheep and cattle, the elites of their breeds. During Wonderwool, however, the barns become like the inside of a kaleidoscope, a sensory overload of colour and texture with nearly two hundred stalls representing sheep breed societies, craft guilds, boutique textile mills, purveyors of equipment for knitters, spinners, weavers, dyers, feltmakers – but mainly yarn, more yarn in a dizzying rainbow of colours than I have ever seen in one place. The choice is overwhelming. The first time I came, I felt like I needed a lie down in a darkened room for the rest of the weekend.

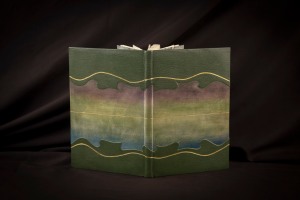

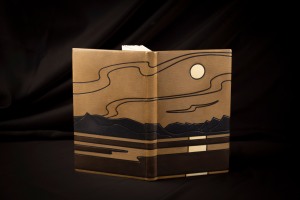

But it is not only the cornucopia of goods for sale which draw the eye. Fibre events like this (similar gatherings in the UK include Yarn Fest in Yorkshire and Woolfest in Cumbria) are an opportunity for people to show off their creations. There are several thousand people here, and seemingly every second person is wearing a handmade scarf, hat, sweater or dress. I could have photographed dozens of examples at Wonderwool, but I settled on these two ladies who had travelled to Wonderwool from Cheshire, resplendent in their stunning, unique creations which incorporate felting and stitching techniques. Fortunately, they were happy to pose for me!

Over the years that I have been coming to Wonderwool, I have noticed trends within the fibre crafts world. For example, a few years ago there was a plethora of yarns made from hemp/linen, organic cotton, and nettle fibres. This year, when I specifically wanted some cotton yarn for a project, there was none to be found, and remarkably little linen either. Neither was there any sign this year of the giant knitting – with yarn as thick as rope, and broomsticks for needles – which was all the rage the last time I went. The theme I could see this year was traceability – there was a strong emphasis on the provenance of the yarn on sale, with information on the flock that the fleece came from and the mill or hand-spinner that had processed it. One vendor was even able to show a prospective customer a picture on her phone of the individual sheep whose fleeces had contributed to the balls of undyed knitting yarn on sale!

I was interested, too, to see an exhibit of natural dyestuffs – a range of plant products which have traditionally been used to dye yarn and fabric – together with the yarn that has been dyed with them. There is increasing interest in natural dyes, with a number of how-to books now available (I have tried it myself, using onion skins to dye some silk fabric a vibrant, autumnal orange) and in view of the environmental impact of conventional (artificial) dyes it was good to see awareness of natural processes being raised in this way.

Despite the name, it’s not all about the wool – one particularly eye-catching stall was selling yarn made from recycled saris. The fabric is ripped into narrow strips, which can then be used to knit, crochet or weave. The colours are luminous.

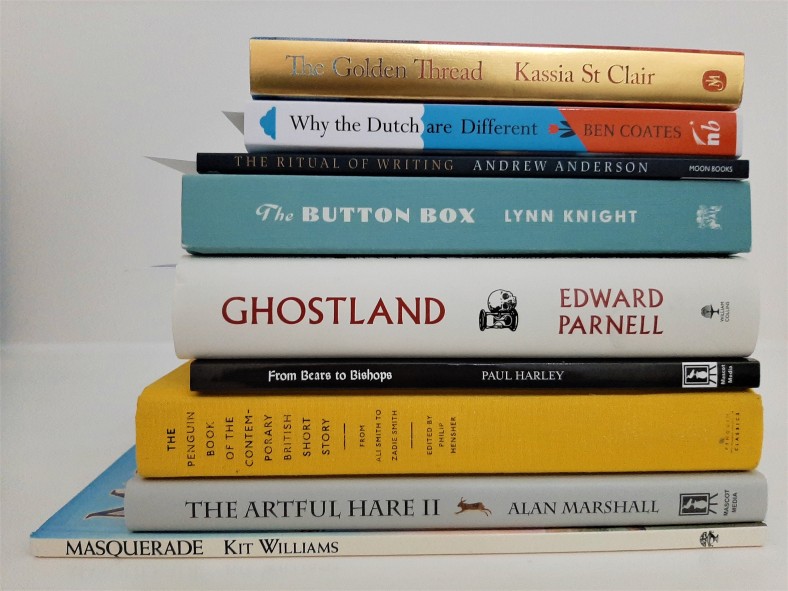

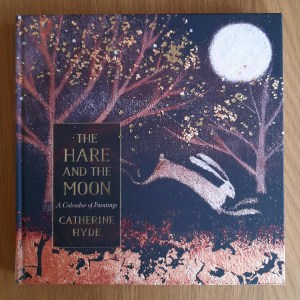

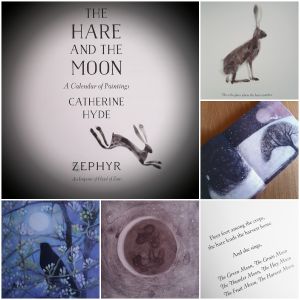

Wonderwool sets out to showcase all the processes from sheep to finished article. Some of the breed societies bring ewes, with their lambs, to the show, and these are always popular. ‘Raw’ fleece – clipped from the sheep last summer – is available for those who like to process and spin their own fibre, as well as combed fibres for feltmakers and spinners who prefer a little less lanolin in their fibres! And, of course, there is yarn – so much yarn. Knitting patterns. Spindles, carders, looms. Knitting needles, crochet hooks, spinning wheels, buttons. Embellishments, dyes, bags of dyed combed ‘tops’ for feltmakers. Knitted toys. Traditional ganseys. Textile art. Yarn. And yet more yarn.

For many of us, though, it isn’t only about the retail opportunity – although I very much doubt anyone leaves empty-handed! There is an aspect of the event which is more like a pilgrimage, a gathering of like-minded people, an opportunity for people to connect around the passion for fibre crafts that unites us. It serves an as annual reunion – in the weeks before Wonderwool, many of us were emailing each other to ask ‘are you going to Wonderwool? Shall we meet up?’ Everywhere, there were greetings, especially enthusiastic this year because of the enforced separation of the pandemic which means it’s been several years since we’ve all got together like this. I arranged to meet up with friends I haven’t seen since the last time I was at Wonderwool, texting ‘I’m here! Where are you?’ and rendezvousing for coffee, where we compared purchases and recommended stalls as well as catching up on our lives. And the world of wool is international – I encountered people from Sweden, Germany, and the USA, as well as from all over the UK. Guilds and groups hire coaches to bus their members to Mid Wales. Conversations start over a shared admiration for a yarn, a texture, a colour. I know I’m not the only one to have made friends through casual meetings at Wonderwool. Here, we all understand the enthusiasm for that amazing sock yarn, that beautiful spindle, the lustre of that fleece. Here, we are amongst our own, our tribe.

I am committed to making this blog freely available, and not putting material behind a paywall. As a writer, I am doing what I love – but I still have to make a living. If you have enjoyed this post, and if you are able to do so, perhaps you would consider supporting my work by making a small contribution via the Buy Me A Coffee button. Thank you!